Take a second look, please, at the title of this paper. There seems to be something wrong, something missing – right? A possibility that comes to mind is the letter ‘a’, which would turn the words into the perfectly plausible (although somewhat unpromising) title: Education as a Key to Innovation. This solution is, alas, rather less than perfect, for if the mistake were a missing ‘a’, then there is a second, typographic error at the head of the page – the ‘e’ should have been upper case – a capital ‘E’. This seems to suggest a different set of solutions to the puzzle of the faulty title – the missing letter should be upper case, and situated at the beginning of the odd-looking “eduction”. Three candidates can be identified quite easily, just by scanning the alphabet from Aeduction to Zeduction.

Deduction as a Key to Innovation would be, for me, an intriguing subject, all the more so due to the prevalent view that the ability for deduction resides somehow in the “square” left side of the brain, at the remote end from the supposed seat of creativity and its sister – innovation. The title opening this paragraph would lead, in that case, to a hope for content which, if nothing else, would provide a welcome change from the non-deductive mainstream of innovation fostering. In fact, this article is about a method, SIT (Systematic Inventive Thinking) which uses a rather analytical – although not strictly deductive – approach to the generation of innovation. Specifically, the aim in this article is to describe one of a set of techniques used in SIT. The name of this technique is Reduction.

So it is Reduction as a Key to Innovation that makes most sense as the correct version of the article’s title. Note that this option – the ‘R’ solution, has a further advantage. If Reduction is indeed the subject of this article and the first word in its title, then the supposed error is actually an example of the application of the very subject of the article on its own title. Indeed, as you can see below, it perfectly matches the SIT procedure for applying the Reduction tool to the task of inventing a new product (in our case – a new title for an article). Here is the procedure for applying Reduction to an existing product, to come up with an innovative version of it:

1. a. List the product’s internal components.

b. Mark those components that seem essential.

2. Remove one or more of the essential components and visualize the resulting “virtual product”.

3. Search for opportunities or benefits that can arise from the “virtual product”.

4. Define the new version(s) of your product, the target market(s) and the new benefits.

5. Adjust each new product according to specific needs.

Note that Amazon and the iPhone are prime (oops) examples of Reduction, as are the older ATM and even contact lenses. In our (more modest) case I started out with the obvious and unexciting “Reduction as a Key to Innovation”, dropped the initial “E” and asked myself what benefits you, the reader, could derive from this truncated title. The result is for you to judge.

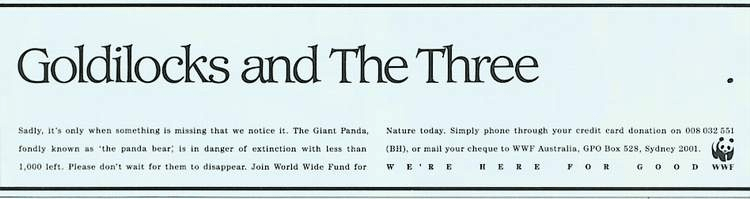

What about the third candidate for the solution of the puzzle in the article’s title? We mentioned before that there is, as you might have noticed yourself, a third letter that can function well at the start of the title, making it into the hard-to-pass-by Seduction as a Key to Innovation. Not completely irrelevant, it must be admitted, for if you’ve chosen to read these pages, and gotten this far into them, it would seem that some act of seduction has taken place. Our work in applying SIT to the field of advertising suggests that there is indeed a connection between se- and re-duction, to the extent that leaving out key elements of a communication, such as an advertisement – as is often done in the case of teasers – entices the viewer into an interaction with the ad, which usually leads to higher recognition, involvement and retention of its contents.

Take the following ad, from a classic campaign created by the fabled Neil French.

The text:

“This page is dedicated to those amongst us

who have learned to recognize quality without peering at a label.”

For those of you who – like me – haven’t, this is a campaign for Chivas regal whisky.

Here is another classic, this time by Ogilvy &Mather Sidney.

Shocking to see that this 20-year-old ad could have appeared today, which points to the limited influence of advertising in general, but both ads exhibit several characteristics common to Reduction advertising: 1) curiosity is aroused; 2) there is respect for the viewer, since he or she are trusted to fill in the missing information by themselves; 3) production costs are absolutely minimal, 4) key elements of the commercial seem to be missing, giving the ad a unique feel.

This last characteristic is, of course, the literal meaning of the use of reduction, and is thus common to any application of the tool, whether in advertising, New Product Development, Problem Solving or any other application. Like many creative tools and most SIT tools, reduction helps its users overcome the well known “Functional Fixedness”, by suggesting that some element of the situation can play a role other than its traditional purpose. But reduction goes one step further and liberates thinkers from an arguably deeper preconception which can be called “Existential Fixedness” – the view that things and situations are defined by an inventory of their components. Reduction, then, in some of its versions, challenges not only your view of what things do, but even of what things are. This is the power of reduction, and also the source of the feeling of unease that it often inspires.

Reduction, as mentioned, can be applied in virtually any field. Actually, it might be an interesting idea to apply reduction to the structure of an article, say by finishing it with no

Historical note: this piece is a slight adaptation to a text written some 20 years ago, for internal purposes, in the days when SIT still used the term “Reduction” for what we now call “Subtraction”. I leave it to the loyal reader to imagine the first paragraphs of an article titled “traction as a Key to Innovation” 😊

Bibliographical note: you may want to read more about Subtraction and several additional tools in the article we published years ago in the Harvard Business Review, called “Finding your innovation sweet spot”. It was at my HBR editor’s insistence that we changed the tool’s name from Reduction to Subtraction. He was right(: