My mother liked to strike up conversations with strangers of all stripes, and it was one of my favorite childhood pastimes to listen in. But sometimes, when they babbled away uncontrollably, she would turn to my sister and me and mumble: “mental constipation, verbal diarrhea”. My professional life provides, alas, many occasions in which I am reminded of this indelicate quip. With a softer approach in mind, I have developed throughout the years a practical tool for managing the contributions of participants in a workshop that I would like to share with you.

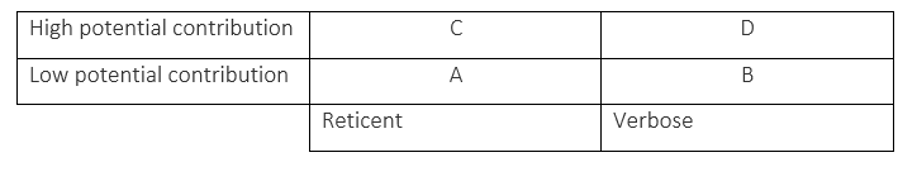

First step: Mentally visualize the participants, each placed in one of four quadrants, defined by two axes:

- Quantity – the amount of air-time they tend to occupy (how often and how much they speak).

- Quality – your assessment of their potential contribution to achieving the goals of the session.

This segments your public into four groups:

Participants in each quadrant require different treatments. Your second step, therefore, is to interact with each group according to the following guidelines.

A’s (reticent with low contribution potential) – Balance OK, no harm to the dynamics, unless there are too many A’s in the room, which means that something is terribly wrong. But even if there are relatively few A’s, it is worth exploring: Maybe an A shouldn’t have been there in the first place? If so, is it too late to release them from this unnecessary commitment? Maybe they can be highly valuable elsewhere? But maybe all they need is to better understand their role in your workshop and what they could potentially contribute. I remember a Plant Manager in Mexico who was sure that the Marketing Manager and her team should be allowed to lead an enthusiastic discussion about new products without any spoil-sport manufacturing comments from him, until I explained that his professional considerations (provided that they were phrased constructively) were crucial guidelines within which the marketing team, and others, could let their imagination fly. He then transformed into a true partner of the marketing participants, helping them convert their ideas into implementable projects.

B’s (verbose with low potential contribution) – Need controlling, because they are misusing the team’s most valuable asset – time. There are many ways, some more subtle than others, to control a rampant B, and your task is as delicate as it is crucial to the success of the engagement. First, there is high potential for hurt feelings, and second, the possibility always exists that there is, in fact, more value in B’s contribution than initially meets the ear.

C’s (reticent with high potential contribution) – Can be easily mistaken for an A and left alone. Thus, their potential contribution is lost, with unfortunate consequences both for them and for the team. An important task for you as facilitator is to find a moment – probably during a break – to conduct your differential diagnosis: is the introverted engineer from R&D an A who shouldn’t have been invited in the first place, or is he an invaluable trove of coaxable, priceless information?

D’s (verbose with high potential contribution) are a facilitator’s best friends. They contribute. They sustain the energy. They give you the (positive) feedback you need. They will extract you from those uneasy moments of general silence. They are truly your allies. But beware of the trap of allowing them to lead the discussion uni-directionally, squelching other voices that may open the more innovative avenues you would like to explore.

In summary, all participants are potentially your friends and allies. A balanced management of “air-time to contribution”, with differential treatment for each and every one of them will ensure that this exciting potential is realized.