Fly High – The Fosbury Flop

Whenever the Summer Olympics come along, I think about the many times I have heard my good friend and colleague, Dr. Jacob Goldenberg, so eloquently tell the story of (one of) the greatest sports innovations in history: the Fosbury Flop.

Common wisdom dictates that evolution does not result in revolutions – this is the difference between incremental innovation and breakthrough innovation. At SIT, we’ve been challenging this fallacy for decades. That’s why I love the true story behind the Fosbury Flop, which proves, once again, that common wisdom is a highly unreliable source for practical conclusions.

The Fosbury Flop? Never heard of it…

In 1968, a young high jumper by the name of Dick Fosbury revolutionized his field by winning the Olympic gold medal with a back-first flop that he himself had invented.

Why do we claim that this was revolutionary? There are several indications…

1) The Official Web Site of the Olympic Movement states: “An athlete will never again invent such a revolutionary style. Since this high jump approach, all specialists have adopted the “Fosbury flop” and the world record of the time, held by Soviet Valery Brumel (2.29 m) was quickly broken.”

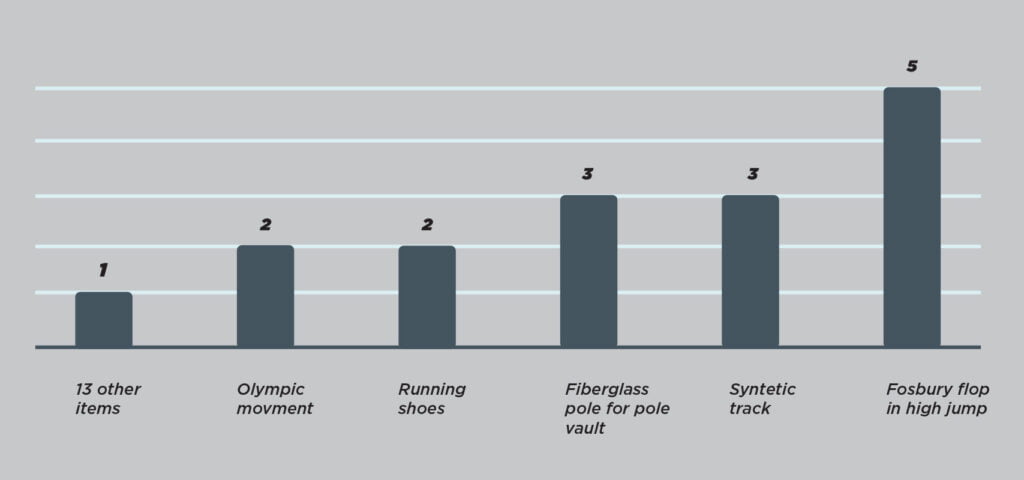

2) Jacob and his colleagues asked 6 sports experts (sports historians, broadcasters, commentators) to each name the 5 most influential innovations in the history of sports. 5 of the 6 mentioned the Fosbury flop.

3) They also asked two dozen judges to rate the innovativeness of 9 sports innovations (including: the game of soccer, swimming techniques, the synthetic track, running shoes, and participation of women) along a list of parameters. The Fosbury flop rated highest overall and first place on its impact on sports, its originality, and its revolutionary nature.

Now that we’ve established that, what’s the story?

At the age of 10, Fosbury learned a high jump technique called the Scissors, which he had copied from some children in his school. At the age of 11, in the fifth grade, Fosbury’s Phys Ed teacher and coach taught all the kids trying out for track to use the Straddle or “western roll” style. After switching to the straddle and beginning all over, Fosbury fell behind the other jumpers competitively. He was very frustrated and asked his coach if he could revert to the old scissors style to get a better result and maybe boost his confidence a bit. His coach conceded.

So Dick decided to try his old style during his next competition. Feeling awkward yet persistent, Fosbury managed to clear his previous best jump of 1.63 meters, and then, facing a new height, knew he had to adjust something. With the scissors style, the jumper typically knocks the bar off with his/her behind, and sometimes with the movement of the legs. To avoid this, Fosbury tried to lift his hips up higher, which dropped his shoulders simultaneously. Fosbury cleared the height. He continued raising his hips until he eventually cleared 15cm higher for a new personal record, and even placed fourth to score points for his team. No one knew what Fosbury was doing as he transformed this old technique into something new, as each attempt was a little different. The opposing coaches checked the rulebook for legality since Fosbury had unexpectedly begun to beat their jumpers.

The next two years, 1964-1965, involved a slow evolution in the technique. Using his curved approach to the bar, Fosbury intuitively began to turn his inside shoulder away from the bar, to get his head over the bar sooner. Thus, the following year, pictures show Fosbury clearing the bar with his body at a 45-degree angle to the bar, no longer parallel to it. By the second year, Fosbury had fully evolved to clearing the bar with his back to it, arching his hips over, then un-arching to kick his heels over and land on his back in the foam pit. In other words, two years of small incremental changes were required for Fosbury to come up with the final, apparently radical, version of his jump.

Dick Fosbury had never envisioned being an Olympic athlete, even up until the 1968 Games. He maintains that he did not set out to change anything — in his own words, “I just wanted to play the game”.

And he did. As the story shows, his is an example that Radical innovations can be the result of a sequence of incremental steps (and oftentimes are – we just don’t notice them due to the perspective of time).

Thanks, Jacob, for sharing this story with me!

How One Man Changed the High Jump Forever | The Olympics on the Record

Back in college, there was a little button — a collectible — that was popular among the more progressive folks on campus, and it would have been a meme if the age were not pre-digital. It was about the size of a quarter, black type on yellow, with the following words: “Question Authority.” Simple enough, right? But the joke among my friends – a young but already linguistically sensitive crowd, always looking for nuance and/or irony – was that the button could be read in two ways. Either the wearer was claiming to be a question authority – an authority on questions — or the wearer was advocating that everyone should join him or her on the mission of questioning people in power. In the end, we learned that the button worked like a Rorschach test. If you were prone to question authority, that’s the message you received.

Back in college, there was a little button — a collectible — that was popular among the more progressive folks on campus, and it would have been a meme if the age were not pre-digital. It was about the size of a quarter, black type on yellow, with the following words: “Question Authority.” Simple enough, right? But the joke among my friends – a young but already linguistically sensitive crowd, always looking for nuance and/or irony – was that the button could be read in two ways. Either the wearer was claiming to be a question authority – an authority on questions — or the wearer was advocating that everyone should join him or her on the mission of questioning people in power. In the end, we learned that the button worked like a Rorschach test. If you were prone to question authority, that’s the message you received. I’m talking about a methodology called Systematic Inventive Thinking (SIT) that was not quite invented in Israel, but has taken root here and is spreading worldwide. It is different – though perhaps complementary – to design thinking, but it’s what they have in common that, from my perspective, makes SIT worth watching.

I’m talking about a methodology called Systematic Inventive Thinking (SIT) that was not quite invented in Israel, but has taken root here and is spreading worldwide. It is different – though perhaps complementary – to design thinking, but it’s what they have in common that, from my perspective, makes SIT worth watching. Inspired by the work of Russian engineer

Inspired by the work of Russian engineer

Once she had a plot, she filled in information and facts from the world around her – places, character names, and so on – all fitted within the same template. One would think that sixty-six murder-mystery novels using the same template would be dull and lose their appeal. On the contrary, Christie’s template constrained her in a way that made her more creative, not less. She is the best selling novelist of all time.

Once she had a plot, she filled in information and facts from the world around her – places, character names, and so on – all fitted within the same template. One would think that sixty-six murder-mystery novels using the same template would be dull and lose their appeal. On the contrary, Christie’s template constrained her in a way that made her more creative, not less. She is the best selling novelist of all time.