Do you want to create an innovation-focused culture in your organization? Are you struggling to make organizational innovation a reality?

Are you tired of wondering why your team’s ideas don’t always seem to pan out as originally planned? Or do your team’s problems actually stem from the idea-generating phase?

There could be countless issues standing in the way of organizational innovation. But the truth is most of these problems are well within your control to fix.

That is, only if you know where to look and how to solve them.

Fortunately, that’s exactly what today’s guide will help you do. We’ll be going over some of the most common mistakes companies make when it comes to organizational innovation and indicate how you can go about correcting them.

DON’T LET THESE MISTAKES GET IN THE WAY OF YOUR ORGANIZATIONAL INNOVATION

To start, you’ll need to take a closer look at your basic approach to innovation.

You do have one, right?

If you’re shrugging your shoulders, let’s start by discussing this all-too-common mistake first.

#1: You have no proper plan in place to support a culture of innovation

You want to create an environment that allows ideas to flourish naturally. That’s great, but so does everyone else.

So, what is your plan?

Without a proper plan in place, you can’t build an innovation-centric culture. It just doesn’t appear overnight or as soon as you say you are innovation-focused.

Instead, you must first create a plan and then brand it. Let’s see why this matters.

#2: You haven’t branded your innovation process

Though your first step may be building your plan, you also need to brand the entire process using a catchy name and a logo to make this abstract process tangible to your team.

It may sound gimmicky at first, but it’s proven time and again to be one of the major contributing factors helping teams successfully innovate.

The concept behind the idea is simple: By branding this process, you’re sending the message to your employees that you’re serious about innovation, and you’re committed to it.

You’re also reinforcing the idea that innovation is now a part of your culture, not just an afterthought. But caution! Correct this and Mistake #3 may be rearing its ugly head.

#3: You have created “Empty Branding”

Companies that heed the call to brand their processes often fall into the trap of spending large amounts of time and money on creating the hype without backing this buzz with corresponding actions. Employees then start to wonder about the gap between declaration and practice, which often leads them to regard innovation with skepticism and conclude that top management is committed only to PR.

So, as you devise your branding and internal communications plan, two things must also happen simultaneously:

- Someone from your team needs to take ownership of the entire process.

- Someone else should be consistently managing the team.

We’ll touch on both points next.

#4: No one has taken ownership of the process

It’s essential that someone take ownership of your innovation process.

Now, this does not mean they’re the only one working on the project. In fact, it’s just the opposite.

All hands are on deck. But the person in charge ensures that a system is in place. It’s branded and weaved into your culture, and it’s properly managed.

If you’re working with a small team, this person could also be the one managing the team as well.

Keep in mind, these are still two distinct roles and should be treated as such. Otherwise, you’ll be making another costly mistake.

The ownership role ensures that the planning is done, and the foundation is properly laid and in place.

The person in the management position ensures that your systems are working and running smoothly. And if they’re not, they’ll be the ones to make any necessary adjustments (more on this next).

#5: No one is managing innovation

Just because you create a system doesn’t mean it’s going to run on its own.

That’s why an innovation manager is key and – depending on your organization’s size – her/his team.

This person helps foster and grow the seeds that have been planted in the initial approach.

To succeed, your innovation Manager(s) should use a “top-down/bottom-up” approach involving both senior management and staff in programs and activities.

Your Manager and/or team will need clear assignment of roles and responsibilities and the ability to monitor that the organizational innovation is actually happening according to plan.

But even with these measures in place, if you’re making this next mistake, these actions won’t matter as much as they should.

#6: You’ve fostered an environment where people are scared to speak up for fear of criticism

In addition to ownership and management, your organization will also need people with facilitation capabilities.

These people help ensure that your employees feel comfortable speaking up — without fear of criticism or judgment.

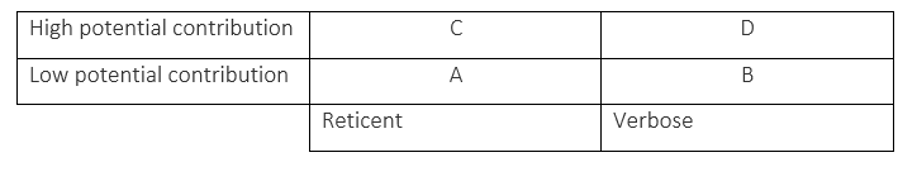

During the group discussion, there will always be employees who speak up more often than others. But it’s essential that these team members don’t overrule the quiet ones.

If you’re creating an environment where people can’t speak up, they won’t. And some of your best ideas may never surface.

To alleviate this phenomenon, take breaks during discussions to moderate any employees who are taking over the conversation and encourage quiet team members to speak up without worrying about what anyone will think.

However, expressing yourself and generating ideas is still only half the battle. You must also use them, or you’ll be making this next error.

#7: You also lack proper systems to manage innovation in your organization

If you really want to see your team’s ideas take off, you need to figure out:

- How you’re going to manage those ideas

- How they will be put in place

- How you’ll measure their viability

- How you’ll gauge if something is working, needs to be scrapped, or just needs a slight tweak (more on this later)

Get these systems in place right away or your best ideas will slip through the cracks.

Speaking of ideas, the way your team ideates to come up with ideas could be another issue holding your innovation back.

#8: You’re still using traditional brainstorming-type methods

Are you still relying on the ol’ brainstorming technique where everyone sits around the conference table and tries to come up with ideas on-the-spot believing that “there’s no such thing as a bad idea”?

This is a huge mistake far too many organizations seem to be making. And their growth — or lack thereof — shows it.

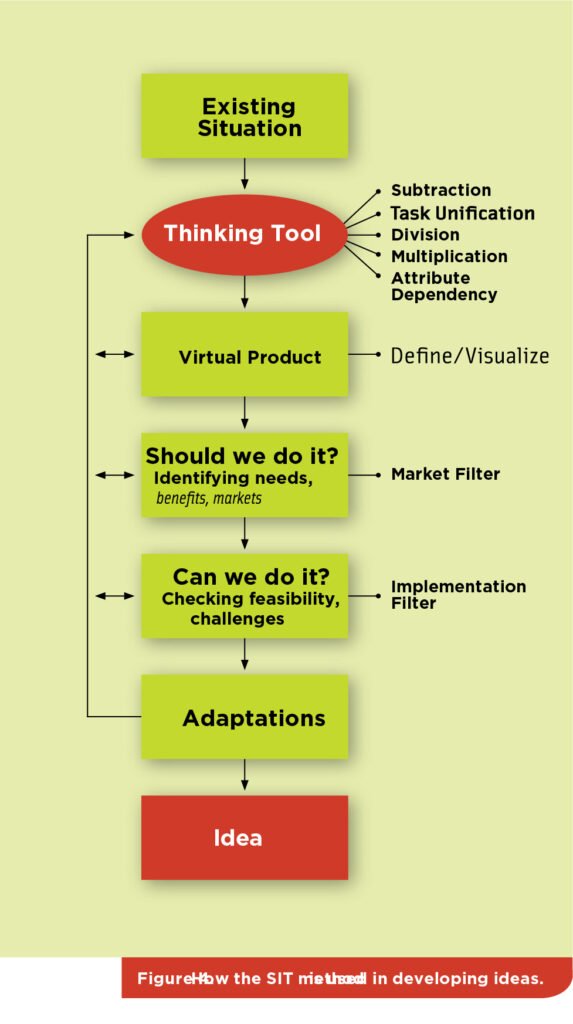

In short, ideation sessions require structure and discipline if you want to break out of existing paradigms and biases.

To do this, you must focus on what you already know (“inside the box”), and then you must look at the problem from a different angle, which is also the next most common mistake on our list.

#9: You’re looking at the problem from the same angle every time

If you’re looking at a problem the same way every time, you’re always going to get the same results.

Take a step back and try to attack the problem head-on using what you know and the fact that your current angle is not working.

If you’ve tried to solve the problem from all sides, maybe you’ve been working on the wrong problem altogether.

#10: You haven’t mapped out the real problem first

If you’re stuck on the same issue and keep wondering why you’re not making any progress, you must ask yourself, “Are we sure this is really the problem?”

Chances are, it might not be. Start creating systems to solve the wrong problem, and you’ll be wasting everyone’s time.

So before you dive into different angles of approaching the same problem, you must first identify that you’re truly tackling the real issue at hand, not merely one posing as the problem.

Only when you correctly identify your true problem can you put your team’s skills to work on fixing it. There are tools that will help you do just that and surprise – finding the root cause is not necessarily the right way to go about it. Actually, it seldom is. Another common issue: you may not be giving your team the tools they need to succeed.

#11: You don’t give your team the tools they need to succeed

Even if you uncover your team’s strengths, if they don’t have what they need to get the job done, your innovation efforts will be wasted. Managers often erroneously assume that if they just put in the relevant incentives – carrots or sticks – their people will be driven to innovate. But no amount of motivation will help people who simply lack the skills and capabilities to innovate. And these can be acquired using the right methods.

And not only are the tools available, but employees can also become adept at using them, and can dramatically improve their organizational innovation capabilities with practice and dedication.

Besides giving your team everything they need to succeed, you also need to encourage communication and cooperation — especially if you have different departments working independently.

#12: Your organization is divided into silos

When business units do not communicate or collaborate, it is easy to lose sight of key insights, miss opportunities for synergies, and greatly decrease the probability of implementing meaningful projects.

Though this may occur in many ways within an organization, it is especially detrimental when it comes to organizational innovation. So, focus on fostering communication and teamwork.

Now, what happens when you create a plan, implement ideas from your team, and still don’t achieve the results you were hoping for?

Do you consider your team’s efforts a failure?

#13: If something doesn’t work, it doesn’t mean you’ve failed

Creating a culture of innovation cannot be achieved without a few failed attempts at implementing new ideas under your belt.

But it’s how you deal with these ideas that matters more than if the actual idea was a total flop.

So many organizations chalk the first (and only) loss as a sign that the idea failed and all others will similarly fail like, but this isn’t always the case.

You may only need a few small tweaks to your idea for it to be a huge hit and avoid innovation mistakes. Building on what didn’t work will only lead to stronger concepts.

If you’re not careful, you’re bound to toss out good ideas simply because the first run didn’t go quite as smoothly as planned and that will cost you.

Our experience has shown us that making an innovation program sustainable and fruitful in the longer term requires an organization to focus on the 7 elements of Organizational Innovation. Many of our most valuable insights have been learned directly from implementing these programs with our innovation partners. We will share more about this model in future articles.

Some of these innovation challenges have to do with the process of ideation itself, while others with implementation, some are more relevant on an individual level, and others more on the organizational level. For this discussion, we can define one set of barriers that stop us from coming up with the right ideas (ideation / individual) and another set of challenges involved in the attempt to implement these ideas (implementation / organizational).

Some of these innovation challenges have to do with the process of ideation itself, while others with implementation, some are more relevant on an individual level, and others more on the organizational level. For this discussion, we can define one set of barriers that stop us from coming up with the right ideas (ideation / individual) and another set of challenges involved in the attempt to implement these ideas (implementation / organizational).

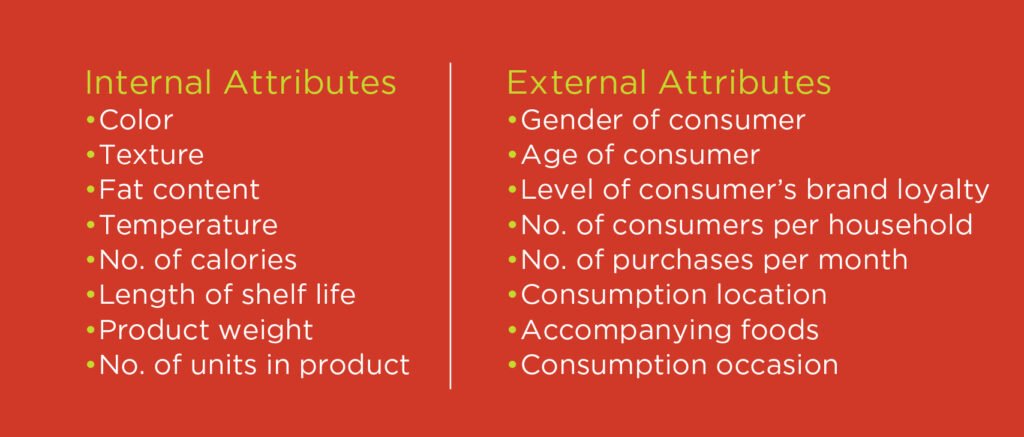

One of these “creativity-facilitating constraints” is the Closed World principle. This principle posits that the only resources for innovating are those that already exist in the product’s immediate environment (Horowitz and Maimon, 1999). These include the essential elements in the product, including its physical components as well as its variables like color or size. The immediate environment of the product is also inventoried for its components and variables. These elements—and only these elements—lead to finding new ideas and solutions. No new types of resources or technologies are allowed to enter into the idea-generation process. Unknowingly, Shemer utilized the Closed World principle when inventing his product. As opposed to his unsuccessful attempts at using other plant-based materials, the secret to his success was manipulating elements within the two leading meat analog bases—soy and wheat proteins, resources already existing in the Closed World. One of the Closed World’s main benefits is that it relies solely on a company’s existing resources and knowledge base, providing a “leg-up” so that it needn’t start from scratch and can more readily assess the feasibility of the solution.

One of these “creativity-facilitating constraints” is the Closed World principle. This principle posits that the only resources for innovating are those that already exist in the product’s immediate environment (Horowitz and Maimon, 1999). These include the essential elements in the product, including its physical components as well as its variables like color or size. The immediate environment of the product is also inventoried for its components and variables. These elements—and only these elements—lead to finding new ideas and solutions. No new types of resources or technologies are allowed to enter into the idea-generation process. Unknowingly, Shemer utilized the Closed World principle when inventing his product. As opposed to his unsuccessful attempts at using other plant-based materials, the secret to his success was manipulating elements within the two leading meat analog bases—soy and wheat proteins, resources already existing in the Closed World. One of the Closed World’s main benefits is that it relies solely on a company’s existing resources and knowledge base, providing a “leg-up” so that it needn’t start from scratch and can more readily assess the feasibility of the solution.

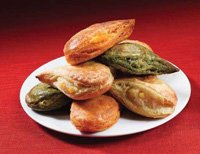

First, the developers defined the Closed World of the product. They broke the product down to its fundamental components and identified available resources. These included the various types of vegetables used for the fillings, as well as dough ingredients such as flour and other grains, salt, sugar, vitamins, and packaging.

First, the developers defined the Closed World of the product. They broke the product down to its fundamental components and identified available resources. These included the various types of vegetables used for the fillings, as well as dough ingredients such as flour and other grains, salt, sugar, vitamins, and packaging.